Photo source: Pixabay via Pexels.com.

I have come to a conclusion. Perhaps if I had thought about it more carefully at first I would not be surprised. But it has only recently occurred to me that a great deal of the disturbance about evolution — yes, no, theistic, atheistic, guided, unguided, young earth, old earth, Darwinist , near-neutralist, whatever! is about human origins. Where did WE come from? Are we descended from primates or not? And what did God have to do with it?

Nobody except specialist scientists would care if a little tree frog was descended from a lobe-finned fish, or was instead specially created with his special poison glands, unless it also had implications with regard to our origin. Not many would care except evolutionary biologists and entomologists if someone claimed that butterflies were descended from a hybridization between onychophorans and insects (an idea that has been refuted, by the way). Most people wouldn’t even know what that meant. They don’t think about where butterflies came from at all.

However, people really do care about our origin, and specifically, whether or not we share common ancestry with apes. They may not put it in so many words, but that’s what their concern with evolution amounts to. People care about their own identity and origin, and aversion to the idea of monkeys as ancestors runs deep in some.

In 2011 when I first got involved in this question I didn’t quite see this. For me, the prior question was whether or not neo-Darwinism was true, whether it could explain the development and diversity of living things.

No Fixed Opinion

I had no fixed opinion about human origins. All I knew was that Darwinian evolution was insufficient to explain life, but I was hazy on the details of what that meant. I believed that God must have guided evolution, if evolution was the explanation for the grand diversity of life. I knew there were arguments for common descent based on DNA similarity between groups. Not that I had ever looked at any sequences, mind you. And arguments against.

I had never considered the question of whether we came from two first parents or from thousands of ape-like primates, because it was not an issue. I accepted the long age of the Earth (I still do), and was prepared to accept that we came from a population of hominins that somehow became human. I had basically never thought deeply about it at all. And I can say with reasonable confidence that the statements in this paragraph would be true for the majority of scientists. But they are no longer true for me.

What follows is a description of how my mind has been changed since then. It began by doubting Darwinian evolution was sufficient explanation for life. What followed was a surprising journey prompted by a seemingly simple question, a journey that led me to think that an original first human pair, aka Adam and Eve, might be possible.

Photo credit: julie aagaard via Pexels.com.

A Not So Simple Question

An email hit my inbox with what I thought was a simple question:

A philosopher I know is looking for a geneticist who can tell him how strong the evidence against Adam and Eve is. Contact him at…

So I wrote, saying I didn’t really know but if I had to speculate…I would go look. The response was ecstatic beyond all proportion. He said he had been looking for years for a geneticist who would answer his question. My word! I thought. What have I gotten involved in now?

I emailed my friend Jay Richards and asked his advice. “Sounds like destiny,” was his laconic and slightly unnerving response.

Enter Ayala

So look I did. The first paper I found seemed to me to be a strong challenge. It was based on the observation that there was a great deal of diversity in some genes, too much genetic diversity to have started from just two people in the time available. The reason I found this paper first is because of the title: “The Myth of Eve: Molecular Biology and Human Origins.”1 Now that was a direct statement of intent, like the slap of a dueler’s glove across the face.

The author, Francisco Ayala, was a former priest and an eminent evolutionary biologist. Ayala claimed that population genetics analysis of an immune system gene called HLA-DRB1 indicated we came from a starting population of at least 100,000, with 32 different versions of HLA-DRB1 at the time of our supposed split from chimps. According to his calculations, the effective population could never have been smaller than 4,000. If he were correct, that would be the end of Adam and Eve. 32 copies of any gene are too many for just two people to have generated or carried. Each person has one or two copies of every gene, so the maximum number of copies a couple like Adam and Eve could have is four.

The way Ayala did his calculations depended on the DNA he worked with having a background level of mutation, a background level of recombination, and a background level of selection. Otherwise his estimates for the amount of evolutionary time passed would be off. Unfortunately, the small part of the gene he chose to study violated all of those requirements. This inflated his estimate for the number of variants, as was pointed out by Bergström et al.2 a few years after Ayala’s work was published. Their own study used a nearby part of the gene not subject to the same flaws, and dropped the estimate of the number of HLA-DRB1 variants at the beginning of humanity to seven. Just seven. But still too many.

This story, plus our protein studies and other work on fossils and chromosome fusion became the book Science and Human Origins, which I co-authored, published by Discovery Institute Press in 2012.3

A Collaboration Begins

That same year I began a collaboration aimed at making a population genetics model for testing the possibility of a first-couple origin with a Swedish population geneticist named Ola Hössjer. We met one December evening in the lobby of a Copenhagen hotel, he with his note pad and pencil and I with a head full of ideas half-formed. I described what I wanted: a mathematical model that could be used to generate and track genetic diversity over time in a population of humans, starting from two. We needed to be able to look for the effects on population statistics of various kinds of things, like number of children born per women, mortality at various ages, migration, tribes, etc. I thought I was throwing an enormous impossible pile on this gentle Swede.

In 2013 I discovered that Bergström’s lab had gone on to sequence a number of full-length variants of HLA-DRB1. They reported coalescence to four lineages, just four, though which lineages they meant is ambiguous.4 That number four caught my eye, though, because that is the number of lineages Adam and Eve could have carried if they were both heterozygous for the gene HLA-DRB1.

A Revealing Tree

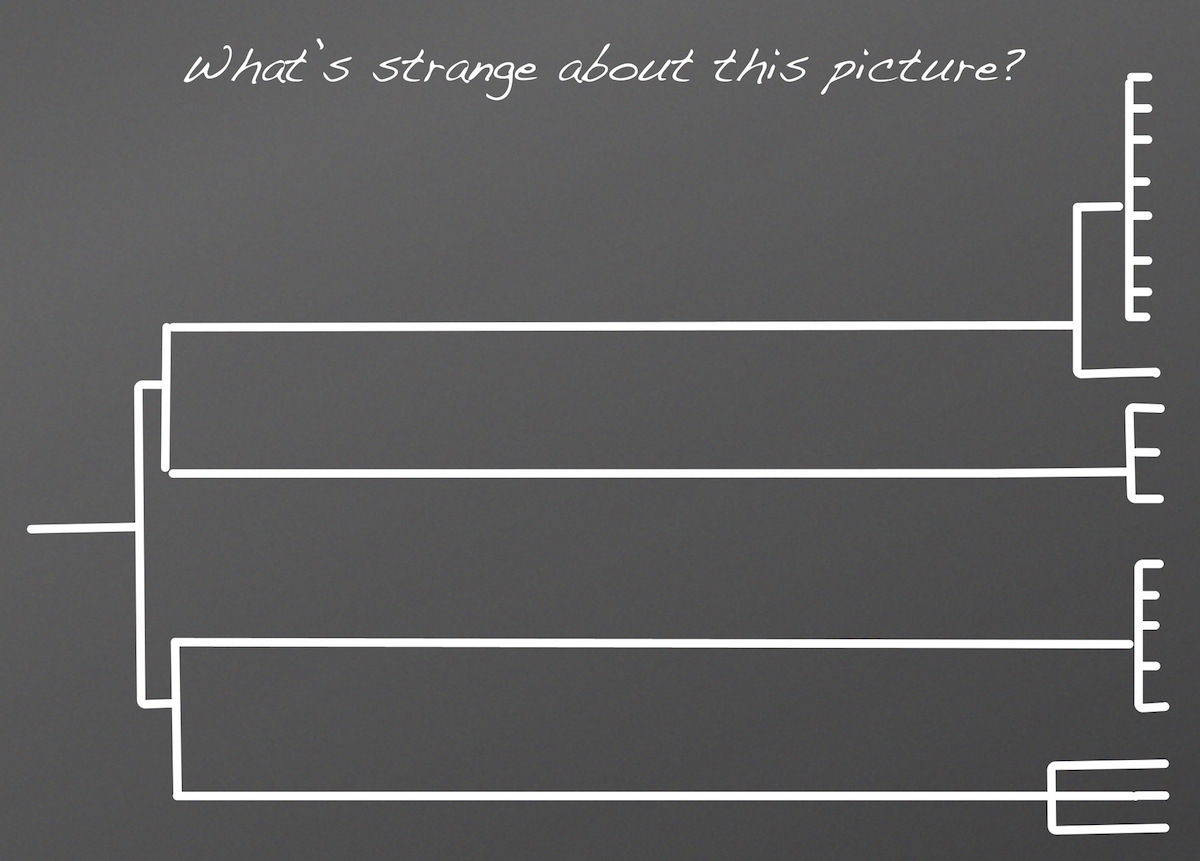

Von Salome et al. had a graph that I stared at for a long time. It was a graph showing the tree of relatedness for variants of the gene HLA-DRB1 in humans. I have drawn a cartoon, exaggerated version here.

When you look from left to right, you are looking from the deep past to the present. The data is on the right. The individual little lines like teeth in a comb represent individual gene variants here in the present. I have drawn 22. We know their DNA sequences, so we can compare them and figure out which are most alike and most different — how they are related. We group them according to family, and then if necessary, group them again.

This is a vastly oversimplified gene tree, but it captures three things. The length of the branches corresponds to time OR genetic distance. What geneticists actually measure is how different DNA sequences are — the genetic distance between them — and then they convert that to evolutionary time by using a factor based on fossil evidence from elsewhere. So when you see really long branches like in this tree, that means the DNA in each branch is distinctive, different from the others. The question is why?

Is it because they diverged over a long time period, or is it because they were made to be different — primordial diversity from the beginning?

*KEY QUESTION*

The other thing to notice is that all the diversity happened really recently. On the real graph, the average age is about 450,000 years. On a scale of 50 million years, that’s lightning fast. A DRB1 explosion.

*NOTE THE AGE*

The last thing to notice is that there are four lineages, four long branches for a very long time (30 million years). Or one could say, four distinct genes with distinct sequences.

*SOUND FAMILIAR?*

When I saw these things, I knew I had something potentially very important. It might be a signal from the distant past of our origin — not from a population of thousands as Ayala had proposed, but from a population of two, perhaps 500,000 years ago, an origin of two, followed by the steady increase and diversification going forward of their offspring.

I was excited!

Photo credit: Lina Kivaka via Pexels.com.

Getting It Done

But still we needed a catalyst. And that catalyst came in the form a new book to be written that had to address “the Adam and Eve question.” A loose coalition came together to brainstorm about the best way forward. We needed genetics, fossils, and an answer to the population genetics challenge. Ola’s model rapidly came together (he’s a wonder!). From that collaboration came two papers, published in 20165,6, that described Ola’s magnificent model, and three chapters for the book.7 At that stage the model had yet to be programmed.

The next phase required someone with programming expertise. In 2017 we found a programmer who showed considerable talent for population genetics. I watched things happen, with amazing speed, offering comments and suggestions as they occurred, but the work was in Ola and the programmer’s hands now.

By the end of 2018 the job was done. All that was left was to see the paper published.

What Was the Result?

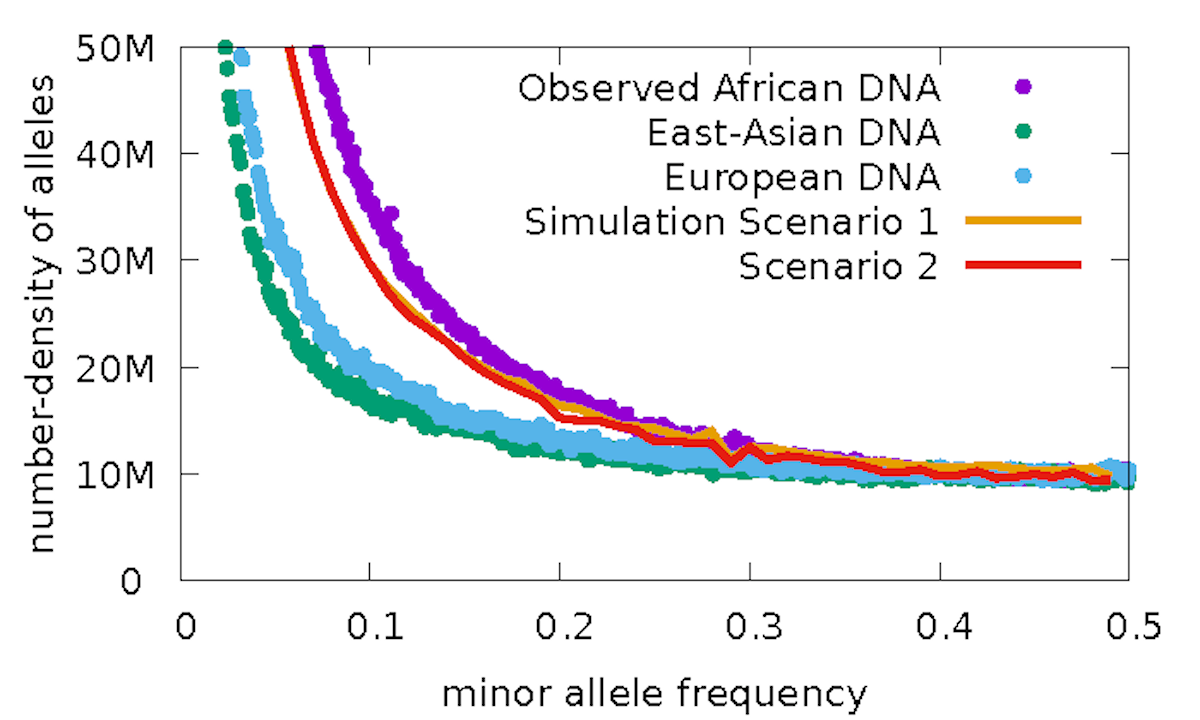

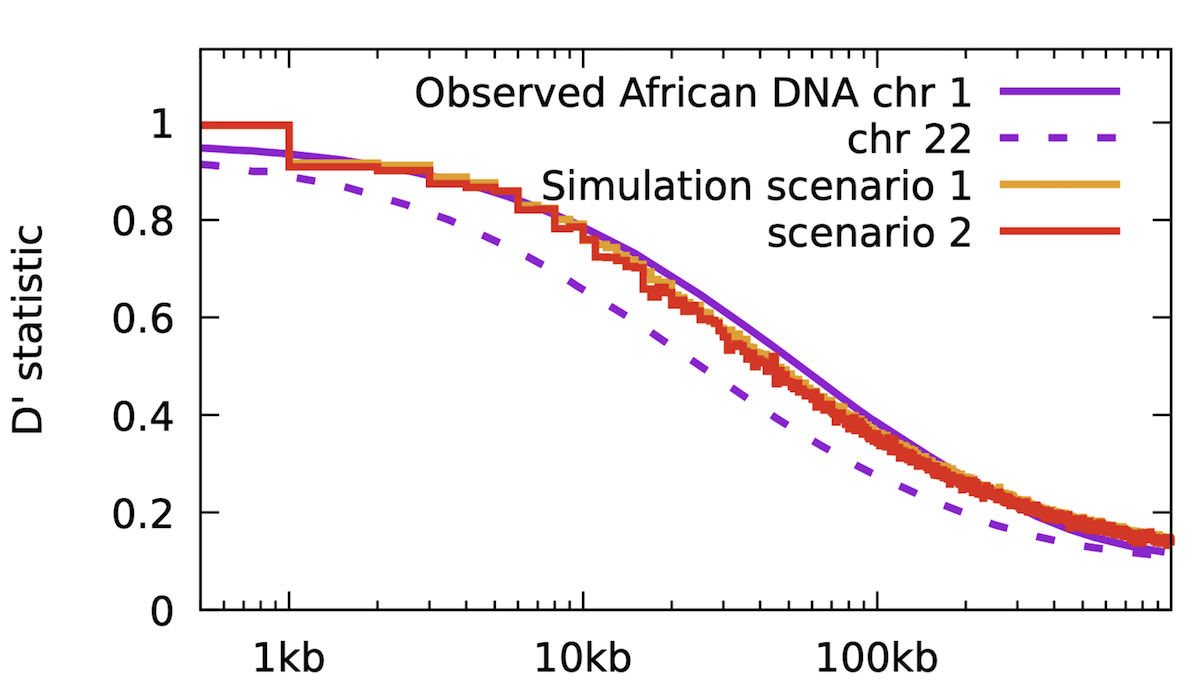

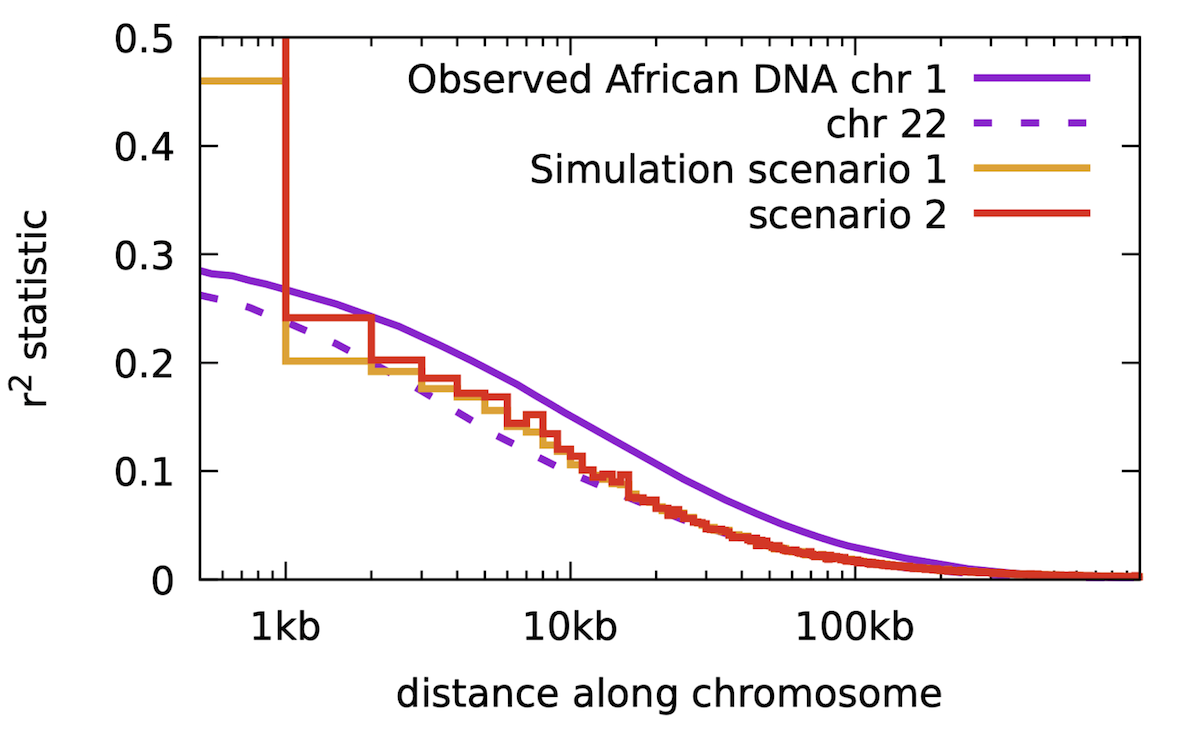

All you need to know to read the result is that the current human population is in purple, green, and blue curves, and our model’s curves are in orange and red. Pretty good fit, eh? We can match current genetic diversity starting from two, using no special tricks. The yellow line is with no primordial diversity; it took 2 million years to reach this level of diversity. The red curve is with primordial diversity; it took 500,000 years. Sound familiar? For the complete results and analysis see the paper here.

It’s very simple. The tree was right. The model showed that a single couple starting with primordial diversity, as the tree had suggested, could match current genetic diversity in 500,000 years. We could have come from a first pair with primordial diversity 500,000 years ago. We could start from two individuals with initial diversity in their chromosomes, then let the population grow at a reasonable rate to a steady state of 16,000. Using standard mutation rates, etc., and no special assumptions, in other words, a parsimonious model, we could duplicate current population statistics like allele frequency spectrum (AFS) and linkage disequilibrium (LD).* These graphs are a beautiful sight — the alignment between actual genomic data with data Ola’s program generates is amazing.

The tree indicated an explosion of diversification with an average of 450,000 years ago. That too is intriguing. The sudden explosion would be expected in a rapidly expanding, spreading population. It is possible it is just the nature of coalescence trees, but not usually so extreme. HLA-DRB1, the gene Ayala and Von Salome et al. studied, is a chameleon-like gene and apparently mutates quite readily.

Is this proof of Adam and Eve? Far from it. It merely shows they might be possible. This model is scientific and as such is falsifiable — just like the claim that we absolutely could not come from two because our genetic diversity was too great has now been shown to be false.

It started with a simple question. How strong is the evidence against Adam and Eve?

I have come to a conclusion. Not as strong as they thought, it turns out.

Photo source: Pixabay, via Pexels.com.

Notes:

- Ayala FJ (1995) The Myth of Eve: Molecular Biology and Human Origins. Science 270: 1930-1936.

- Bergström, T. et al. (1998) Recent Origin of HLA-DRB1 Alleles and Implications for Human Evolution. Nature Genetics 18: 237-242.

- Gauger A, Axe D, Luskin C. (2012) Science and Human Origins. Discovery Institute Press.

- Von Salomé et al. (2007) Full-length Sequence Analysis of the HLA-DRB1 Locus Suggests a Recent Origin of Alleles. Immunogenetics 59: 261–271.

- Hössjer O, Gauger AK, Reeves C (2016) Genetic modeling of human history Part 1: Comparison of common descent and unique origin approaches. BIO-Complexity 2016(3):1-15. doi:10.5048/BIO-C.2016.3

- Hössjer O, Gauger AK, Reeves C (2016) Genetic modeling of human history Part 2: A unique origin algorithm. BIO-Complexity 2016(4):1-36. doi:10.5048/BIO-C.2016.4

- Theistic Evolution: A Scientific, Philosophical and Theological Critique. Edited by: J. P. Moreland, Stephen Meyer, Wayne Grudem, Christopher Shaw, and Ann Gauger. (Crossway, Wheaton, IL)

*AFS has to do with how many rare and how many common variants there are in the population, and how they are distributed. The rare ones are bunched up as a sharp peak to the left of the graph because while each variant is rare, there are many rare variants. The LD graphs are more complex. They are measures of recombination — how DNA shuffles itself into new combinations in each generation.

Cross-posted from Dr. Gauger’s website, Making Notes of the Moment. A version of this article appears in Salvo 51.